Barks Blog

Very Clear on the Concept

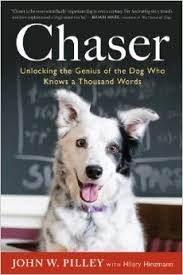

Jana started learning concepts and putting things into categories way back when she was a puppy, before Chaser was even born. Chaser is the most famous “categorizing” dog; she has learned the names of well over 1,000 items and can group them into the right categories: toys, balls, Frisbees, etc. In addition, she has demonstrated an understanding of grammar, correctly taking one item to another, for example. She also can watch, remember, and imitate complex strings of behaviors. Chaser’s story is told in Chaser: Unlocking the Genius of the Dog Who Knows a Thousand Words. It’s also told in a couple of research papers by her dad, Dr. John Pilley.

Jana started learning concepts and putting things into categories way back when she was a puppy, before Chaser was even born. Chaser is the most famous “categorizing” dog; she has learned the names of well over 1,000 items and can group them into the right categories: toys, balls, Frisbees, etc. In addition, she has demonstrated an understanding of grammar, correctly taking one item to another, for example. She also can watch, remember, and imitate complex strings of behaviors. Chaser’s story is told in Chaser: Unlocking the Genius of the Dog Who Knows a Thousand Words. It’s also told in a couple of research papers by her dad, Dr. John Pilley.

Dogs are pretty smart. As amazing as Chaser is, I didn’t need her to convince me that dogs are brighter than we usually give them credit for — and that dogs can understand both individual words and broad concepts. But Chaser is an inspiration.

After learning about Chaser, I started playing around with concept learning again. Early on, I taught Jana to think conceptually about tasks — teaching her to “open the door,” for example, then letting her decide whether she needed to tug a rope on the handle or push on the door with her paws or nose to accomplish that. Same goes for “close the door.” Rather than dictate to her, with a specific command, what action to take, I taught her the basic steps, then gave her a task and let her figure it out.

That worked well, so we moved on to other concepts — bigger and smaller, for example. I got sets of items that were the same except for their size, and asked her for the bigger or smaller ball, cup, dumbbell, etc.

The latest concepts I have worked on with Jana and Cali are “shoes” and “get the other one” — obviously wanting two matching shoes. I still end up with more shoes than I can wear at once (maybe they think I, too, have four feet?), but Jana and Cali definitely get the concept of shoes. They know which ones I wear for our morning walk, too, and eagerly bring them to speed up preparation for our departure.

Another idea that Chaser inspired was my effort to teach the dogs to associate an item with its picture, crudely drawn (I’m no artist) on a card. Jana very quickly got that concept — as well as the concept of asking for what she wanted by pointing to or picking up the card. I have to keep the “popsicle” card hidden unless I have a large supply of the coconut-water ice cubes it represents.

Chaser’s dad is also an inspiration. In his book and research articles, Dr. Pilley emphasizes the way he taught Chaser so many words and concepts — he made training fun and rewarding. His training was very methodical and well-documented, and certainly repetitive. But he was careful to be consistent and positive — and, above all, keep it fun. Chaser got lots of play rewards and, besides the formal language training, she got play time with her dad and chances to do things she really loved, like herd sheep.

This might seem obvious, but too many dog owners and even trainers put little effort into keeping training fun and relevant. Seeing how eagerly Jana and Cali, my two dogs, respond to new tasks or new approaches to training reinforces what Chaser and Dr. Pilley teach us.

Recently, again thinking of Chaser, we’ve tried our hand (and paws) at learning by imitation. Here, I think competition ups the motivation. I start with a pocketful of treats. I tell them to watch, then do something simple that both girls know how to do on cue and can easily imitate, like turn in a circle or sit on the floor. I then say, “Now you do it!” Jana caught on very fast (anything for a cookie!). But Cali still sometimes tries a bunch of tricks before hitting on the right one. I am not sure she has grasped the concept of “copy me” yet. But here, I confess, I’m not emulating Dr. Pilley’s disciplined, regular training or consistency, and the sloppy results show that. On the other hand, Jana, Cali, and I always have a lot of fun in our impromptu “copy me” sessions.

I don’t think we’ve come close to figuring out the limits of what we can teach dogs. As Dr. Pilley discovered, what holds us back is not any limit of their abilities or willingness to learn; it’s our lack of creativity in devising new things to teach them and new ways to teach it. And, of course, coming up with rewards that the dogs really want — the walk once both walking shoes are delivered, munching coconut popsicles in the yard — speeds up the process considerably.

[Note: I would be happy to share any academic articles referenced with readers who contact me; I cannot post links to them, however, unless they were published with open access.]